Peter Carey has one key piece of advice for white novelists attempting to write about Indigenous Australia: “Do not make a dick of yourself.”

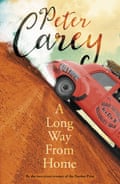

It’s all anyone wants to talk to him about at the moment. Carey’s new novel, A Long Way From Home, is his first attempt at tackling the living legacies of colonialism in Australia head-on, including genocide, slavery, rape, the Stolen Generation – things he admits he’s been silent about for most of his life.

It was age that turned him around on this, he says – the realisation that Indigenous dispossession is a critical part of his Australian identity, whether he likes it or not.

“It’s no good not engaging with something that you’ve been intrinsically involved in. You wake up in the morning and you are the beneficiary of a genocide,” he tells Guardian Australia. “I’m an Australian writer and I haven’t written about this? Well, that just seems pathetic to me.”

Although he was aware of the debates about cultural appropriation in literary circles – such as the controversy over Lionel Shriver’s speech defending the practice at the 2016 Brisbane Writers Festival – Carey says he didn’t allow them to tie him down creatively.

“It’s my job to take creative licence, and it’s my job also to imagine what it is to be ‘other’, and it’s my job to do it in such a way that I’m not making a dick of myself.”

It’s instantly clear upon meeting Carey that he is not a man shy of voicing his opinion. He has little reason to be. At 74, he is one of Australia’s most accomplished writers, with 14 novels, two Booker prizes, three Miles Frankin awards and two Commonwealth Writers prizes under his belt. His 2000 novel, The True History of the Kelly Gang, is poised to be made into a film, only the most recent of his works to make that leap. So why would he beat around the bush?

He is scathing, for example, about big business: “Amazon doesn’t give a fuck about the writers,” he says, of the retail juggernaut’s impending Australian launch. “They don’t care if they’re making the books cheaper, and if that means the publishers are making less money, and that means the publishers can pay the writers less, and so the writers can have less time to write and the culture is being impoverished. But no one seems to care about that very much.”

His opinions about culture don’t confine themselves to literature, either. “Culture is the way for a country to know itself. You can look at the central business district of Sydney ... and you can know that the people who designed those buildings and paid for those buildings and planned those buildings have not the least fucking clue about culture or human life on the planet otherwise they wouldn’t make these dark, rotten, life-defying environments in one of the most beautiful cities in the world.”

When it comes to approaching difficult topics in his fiction, he is crystal clear: “You do the work and show respect and you have the patience. And you do not make a dick of yourself.”

In the case of A Long Way from Home, that work involved engaging the help of experts including anthropologist Catherine Wohlan from Australian National University; going out to the Kimberley region to spend time with Indigenous communities; and taking the feedback of Indigenous readers, such as Steve Kinnane. “I can just try and act thoughtfully, decently and open myself up to criticism, while I’m writing [the book], from people to whom that might be of vital importance,” he says.

Readers might be forgiven for wondering, from the opening passages of A Long Way From Home, what exactly happens in the novel to spark all this conversation. It begins, after all, in the 1950s, in the white rural Victorian town of Bacchus Marsh – Carey’s own hometown, and a tiny detour on the road between Melbourne and Ballarat. The sparkling, practical, decisive Irene Bobs, her car salesman husband Titch and their two children have just moved next door to the bookish Willie Bachhuber: a disgraced teacher with an occasionally explosive temper, who is hiding from his child support payments.

The three of them strike up a friendship of sorts, and decide to enter the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trial, a real event – albeit no longer existing – concocted by a fuel additive company, in which workaday cars were driven thousands of kilometres to some of the most remote parts of Australia in order to test their reliability.

Carey’s parents were dealers for General Motors, and he remembers the Redex trial coming through the town when he was a kid, but he is adamant this isn’t a rewriting of his own childhood or an exercise in nostalgia: “Bacchus Marsh is sort of there because it’s lying on the floor and I can use it,” he says. Still, he drew on the family for critical information, such as how to finance a car dealership, or a very meticulous description of pulling apart a 1953 air cleaner on a Holden.

In writing the novel, Carey repositions the Redex trial as a kind of colonial marking, describing his book as essentially two maps, spliced together: “We’re pissing around the border of our territory, defining land and mapping it. And I thought, well, there’s another sort of map that they’re going over.”

It’s a solid 150 pages before the parallel narrative, that second map, begins to reveal itself. It would be a spoiler to say too much about how or why, but the Indigenous stories Carey makes use of in the second half of the book are startling, and the way the novel takes the reader into that world is clever and disarming.

“I didn’t go anywhere too deep,” he says. “The stories that I felt best about were when Indigenous people had appropriated [European stories] ... the general notion of the colonised biting back.”

Many of his novels deal with questions of Australian identity, but if there’s continuity across his oeuvre he says that’s for readers to divine. “I want every book to be a completely different book.”