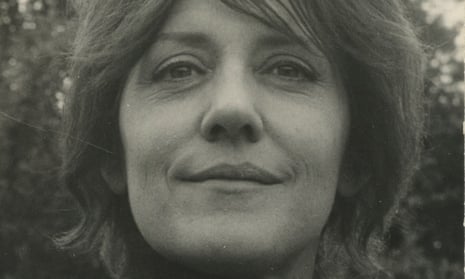

The painter Duffy Ayers, who has died aged 102, was the last survivor of the lively and distinguished community of artists who lived and worked in the Essex village of Great Bardfield from the 1930s to the 60s, and which included Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden, John Aldridge and Michael Rothenstein.

Duffy was a gifted portrait painter within a quiet realist tradition, but her best work was inflected with a subtle French touch of intimism. This set her in some ways apart from most of the artists around her, whose linear naturalism and homely rural subject matter was distinctly English. Her portrait of Ravilious’s wife, Tirzah (1944), is well known: sharply observed, it is at once coolly objective and poignant.

She was born Betty FitzGerald, with an identical twin, Peggy, in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. Their father, William FitzGerald, the feckless brother of the Irish nationalist politician and poet Desmond FitzGerald, abandoned the family when the twins were very young. Their American mother, Laura (nee Farlow), felt she had no alternative but to leave her daughters in a convent school on the Kent coast while she went to teach English in Turkey.

While the other pupils went home for their holidays, the FitzGerald girls stayed with the nuns, who treated them, they recalled, with great cruelty and starved them of affection. The girls did not recognise their mother on her return after seven years’ absence. Emotionally, Duffy was deeply scarred by this long childhood experience but it consolidated in her a remarkable stoicism and strength of character, and she was herself the gentlest of women.

In the early 30s Duffy attended the Central School of Art in London where she met Rothenstein, later to become one of the leading printmaker-artists of his generation. They married in 1936 and moved to Great Bardfield in 1941. Duffy’s emergence from the extreme unhappiness of her schooldays no doubt deepened her empathy, during their first years together, with Michael’s slow recovery from the melancholia of myxoedema (arising from a thyroid condition) that had afflicted him throughout his 20s.

Duffy did little of her own work during these years, but she collaborated with Michael on large-scale paintings, and later assisted his printmaking. During the second world war she made few paintings of her own, but worked at times with the designer Peggy Angus on wallpaper designs.

Later she taught art to the local women of the Women’s Institute. She proved to be a gifted teacher, and encouraged original work of remarkable quality. She had begun painting portraits, too. During the war she maintained a lively correspondence with Robert Graves, a pre-war friend, who by now was living at Deya in Majorca. Her son, Julian, later founder of Redstone Press, was born in 1948, and daughter, Anne, who became an artist, in 1949.

By the mid-50s, Great Bardfield had become famous for its popular Open House exhibitions, initiated in 1951, when several of its artists were employed on murals and design work for the Festival of Britain. For several years, for a summer fortnight, thousands of art lovers descended on the village to traipse through the artists’ houses, delighted by a figurative English modernism that was accessible and stylish, often depicting the life of the village and the landscape around it. During the 40s and early 50s Duffy was a lively presence at the heart of this social and artistic activity. Michael had by this time set up printmaking facilities at Ethel House on the High Street (later enlarged with a studio extension by Frederick Gibberd).

In 1955 Duffy and Michael separated, and they divorced in 1956. Duffy left Great Bardfield, and stopped painting for many years. After her second marriage, in 1957, to the graphic designer Eric Ayers, she moved to a Georgian house in Bloomsbury, central London, where she lived for the rest of her life. Happily, Duffy began to paint again in the 80s. She showed regularly at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions, and in commercial galleries.

In 1994 the Fry Gallery in Saffron Walden, Essex, which specialises in Great Bardfield artists, devoted an exhibition to her work, and it now holds several of her paintings in its permanent collection. Duffy sold virtually everything she painted. Her most characteristic subjects were of solitary female figures; some were of people she knew, others were fictional. Some featured nuns; unlike those of Gwen John, these most often have their backs to the viewer – the distress of an abandoned childhood was never forgotten.

After Eric died in 2001, Duffy carried on painting until a fall left her frail. In 2006 an Australian couple, Sven Klinge and Belinda Murphy, moved in as temporary carers; they stayed for 11 years. They kept Duffy alive and alert, steered her through many interviews about her years in Great Bardfield and monitored her increasing dementia. Despite the late onset of blindness, her final decade may well have been one of her happiest.

She is survived by Julian, Anne and four grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion