Germany Pays Dearly For Failed Energy Policy

US drivers may complain about the cost of filling up, but the epicenter of the energy crisis is Germany. The world’s third-biggest exporter (behind China and the US) reported a monthly trade deficit for the first time in over thirty years. Higher energy prices hit in two ways – Germany is spending much more to import its energy, the result of its strategic blunder in relying on Russia. And its manufactured products are costing more to produce, raising the prices of their exports which is losing some sales.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that Russia intends to exploit its strong hand on energy in ways likely to maximize Germany’s economic pain. An energy strategy that saw fit to rely on Nord Stream 2 was already naïve. Following western sanctions on Russia, Germany still seemed to believe that the natural gas would keep flowing conveniently up until alternative supplies were in place. Decades of German political leaders have turned out to be misguided.

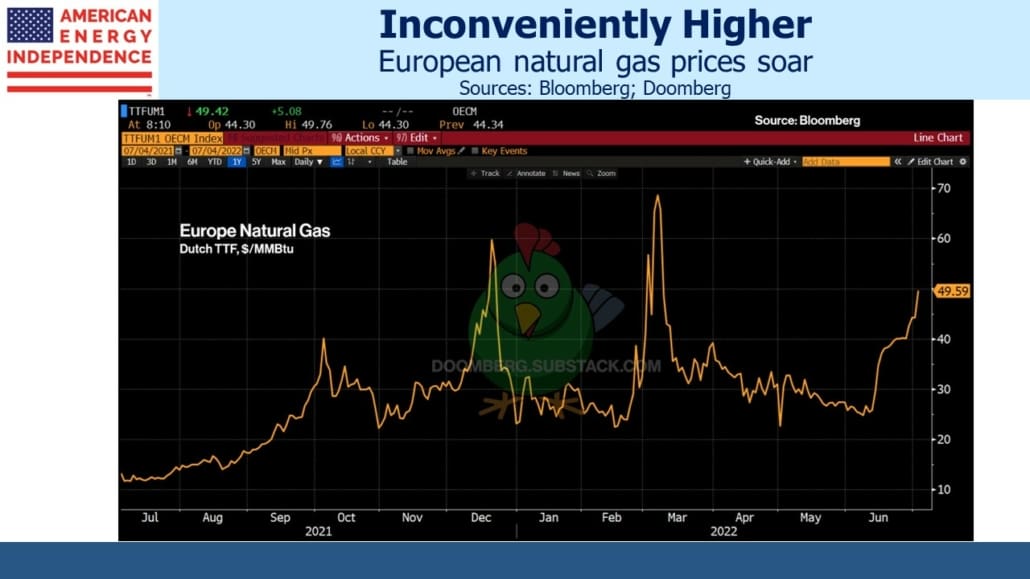

Coincident with Germany’s unfamiliar trade deficit and the cause of it is rising natural gas prices. The Dutch TTF futures contract is at almost $50 per million BTUs, more than five times the US benchmark. Germany’s mittelstand exporters, as efficient as they are, will struggle under such circumstances.

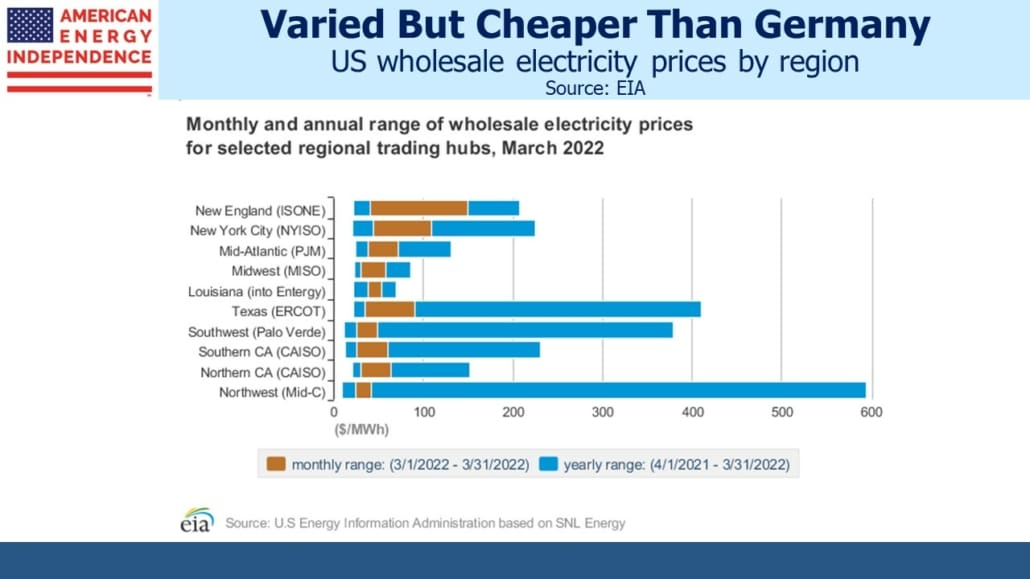

The economic pain is most apparent in power prices – 4Q22 electricity is approaching €400 per Megawatt Hour (MWh). US prices vary widely by region and time of year but are usually a fraction of Germany’s and rarely equal. Germany is preparing to bail out power companies that are having to make up for undelivered Russian gas on the open market while unable to pass those higher costs along to customers.

JPMorgan recently revised down its forecast for Germany’s 2H22 GDP to 1.5%.

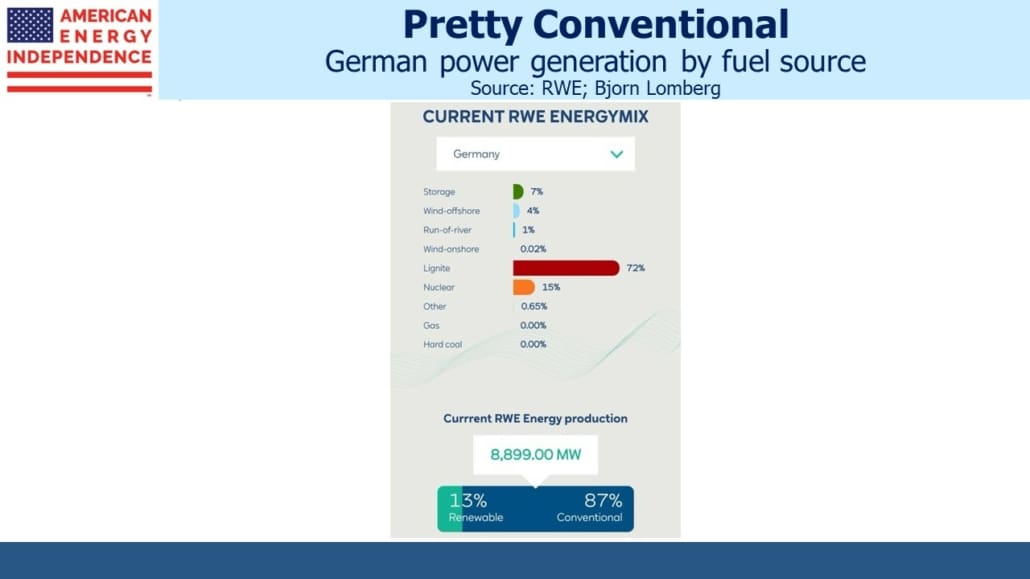

It’s not only Germany’s reliance on Russia that has caused problems. The “Energiewende”, or energy transformation, represents a huge public commitment to reduce Germany’s CO2 emissions with very little to show for it. Over the past two decades, vast investments in solar and wind have lowered the fossil fuel contribution of Germany’s primary energy use modestly, from 84% to 78%, as recorded in Vaclav Smil’s How The World Really Works.

Japan’s 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster prompted the Merkel government to phase out nuclear power, which further exacerbated their vulnerability to Russian supply.

Germany is on track to show the world how much economic damage a disastrous energy policy can inflict on its citizens. Their embrace of policies to combat climate change is based on assumptions such as the EU’s, which anticipates global per capita emissions declining by half by 2050, even though over the past thirty years it’s risen by 20%. As Vaclav Smil notes, “…most of the power to enact meaningful change will lie more and more in the modernizing economies of Asia.”

One result is that Germany has turned back to reliable energy (ie not renewable) such that one day recently 72% of its power generation was from coal.

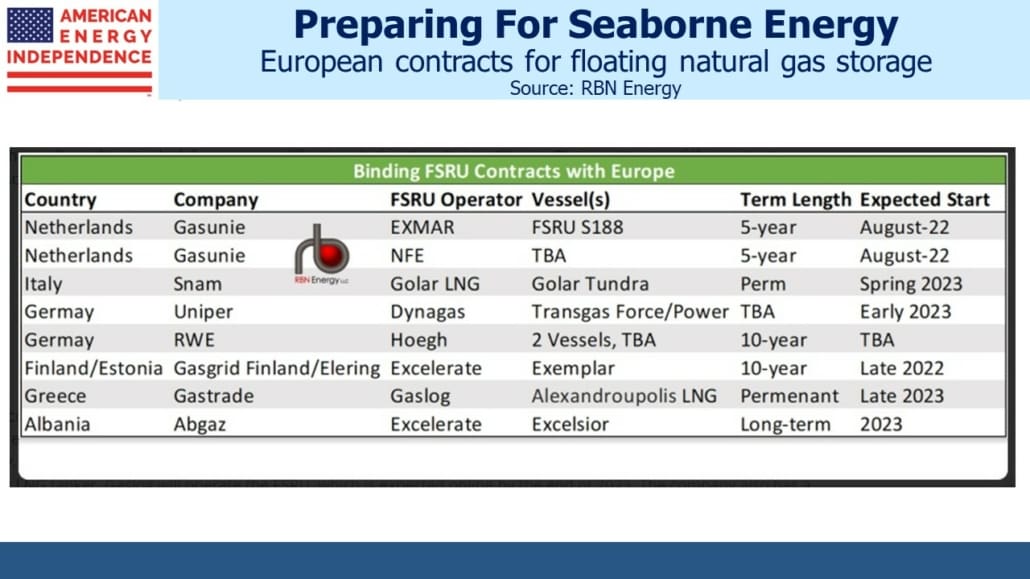

Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs) are an important near-term solution to Europe’s energy crisis. They allow the relatively fast import of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) since the onshore connectivity can be built in just a few months. A full-blown regasification facility takes at least three years. Germany is building two of them but has also leased two FSRUs for more immediate relief.

Building LNG infrastructure for export and import is expensive and time-consuming, with little alternative useful purpose. Long-term contracts provide visibility for buyers and sellers, which also makes the sector appealing to investors like us. Some of Europe’s LNG demand will be met by America in the coming years.

However, European negotiators remain constrained by an ambivalent attitude towards natural gas, in that they want it now, but they want to be able to reduce their consumption in the future when they believe solar and wind power can plug the gap. This has led to protracted and so far, inconclusive negotiations with Qatar, with the Europeans balking at Qatari demands that they sign twenty-year contracts. The EU still retains faith that cheap, long-term battery storage will eventually be developed in enough size to power a city for a few days when it’s cloudy and calm.

Europe’s energy crisis has prompted more decisive action from Asian buyers, who aren’t as confused about their long-term energy needs and regard the EU as potential competition. As a result, they have been acting more quickly. China Gas just announced a twenty-year agreement to buy LNG from NextDecade’s proposed Rio Grande facility, which is increasingly likely to move ahead.

Germany’s energy policy offers little worth emulating, but its exposure is creating opportunities for US LNG exporters.

More By This Author:

Liberal Energy Policies Remain Good For InvestorsMarket Volatility Is Becoming Normal

The Fed Can’t Afford Two Mistakes

Disclosure: We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that ...

more