Why Do Stocks Suffer When Interest Rates Rise?

US EQUITIES OUTLOOK:

- The rapid rise in US Treasury yields has coincided with a steep decline by the major US stock markets.

- Rising interest rates reduce the net-present value of future cash flows, per the traditional discounted cash flow model.

- Companies with high debt burdens and low (or no) profitability tend to suffer most during periods of higher interest rates.

A CHANGING MACRO ENVIRONMENT

The majority of 2022 has proved to be a difficult environment for risk assets. US stock markets, led by the Nasdaq 100, were down around -30% year-to-date (if not more). The finger pointing to assign blame has been intense. It’s because of the Federal Reserve’s missteps on inflation; or the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Or China’s zero-COVID strategy, upending the global supply chain; or the massive fiscal spending undertaken during the early months of the pandemic.

The truth of the matter is that, while narratives are abundant, the root cause is fairly simple, if not common from a macro fundamental perspective: rising interest rates. Whatever the reason for the rise in interest rates is not the focus of this discussion per se, but rather how rising interest rates impact investors’ and traders’ risk appetite in financial markets.

THE FED MODEL

In the post-World War II era, US equity markets have had a higher annualized return than US Treasuries. However, stocks also carry more risk, and thus returns have been more volatile. Specifically, the standard deviation of stock market returns has been higher than those of the bond market.

While stocks carry additional risk relative to bonds, the expected excess return of stocks over bonds makes them a potentially more appealing investment target. One way to measure this trade-off is by using the Fed Model, which compares the earnings yield (E/P; the inverse of the P/E ratio) of the S&P 500 to US Treasury 10-year yield.

As long as the earnings yield of the broader stock market remains higher than the yield on bonds, then it would follow that investors would favor stocks over bonds. However, if the S&P 500’s earnings yield drops below the US Treasury 10-year yield, why would investors take on additional risk to earn a lower return?

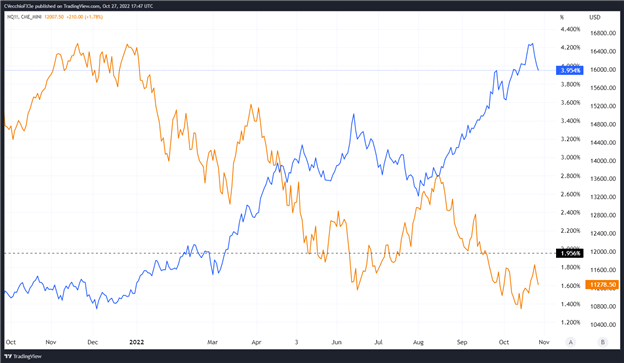

US NASDAQ 100 VERSUS US TREASURY 10-YEAR YIELD

Technical Analysis: Daily Chart (October 2021 To October 2022) (chart 1)

So, the rise in US Treasury yields throughout 2022 has provoked a re-think in how people are allocating their funds: bond returns are comparable to those achievable in the stock market, and depending upon one’s own risk tolerance, the rise in bond yields may be enticing enough to have forced a shift in asset allocation.

FUTURE CASH FLOWS LOSE VALUE

But the decline in US stock markets during a period of higher interest rates is not just about the relatively more appealing return profile of the bond market. We need to crack open our finance 101 textbooks to get to the heart of the matter: the discounted cash flow (DCF) formula.

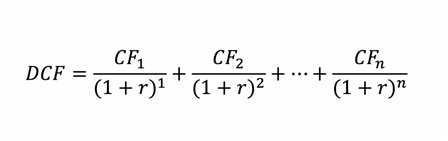

Discounted Cash Flow Formula

The DCF formula measures the cash flows in various years and discounts them by the expected interest rate at that interval in time to find the net-present value of all future cash flows: CF are cash flows; r is the interest rate; and n is the interval in time. Note how r is in the denominator: that means as interest rates increase, the net-present value of the corresponding CF is reduced.

Thus, in an environment where interest rates, as determined by US Treasury yields, are rising, future cash flows that a company produces are worth relatively less today. For companies that comprise US stock markets, rising interest rates means that they are theoretically producing a smaller return in the future. If a company is going to be making less money in the future (in present value terms), then its equity is worth less. And if its equity is worth less, then its stock price suffers.

This relationship is particularly bad for smaller, fledgling companies with relatively minimal cash flows, and is especially bad for companies that are not cash flow positive at present time. Companies that are still in their early stages of growth, those seeking to achieve advancements that would change industries or the economy – newer tech stocks, for example – tend to suffer even more because they don’t have significant cash flows and might carry a great deal of debt.

LONG OR SHORT DURATION?

Stocks, by their nature, tend to be considered “long duration” assets. Conceptually, duration can be boiled down to this: if I invest $1 today, how long will it take to get back? As interest rates increase, assets with longer durations tend to suffer more; the net present value of future cash flows is reduced, therefore it will take longer for the company to return the $1 you invested today.

We’ve previously discussed why Cathie Wood’s ARKK fund, comprised of investments in companies that tend to be recently founded, having just gone public, don’t have significant established revenues and cash flows, and don’t have substantial pricing power within their industries, is performing so poorly in the first six-plus months of 2022. ARKK is basically invested in the longest long duration assets in the market!

The DCF formula explains ARKK’s problems succinctly, and those of the broader stock market, in particular, the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100: the companies don’t have significant (or any) cash flows, and as interest rates rise, their net present value drops quickly.

More By This Author:

FX Week Ahead: BOE, Fed, RBA, Rate Decisions; Canada Jobs Report; US NFP

Central Bank Watch: BOE & ECB Interest Rate Expectations Update; October ECB Meeting Preview

FX Week Ahead: Chinese National Congress; Canada, Eurozone, New Zealand, UK Inflation Rates